Remembering Indigenous Peoples: Higher Education's Commitment to Native Roots

Introduction

Most people do not consider the extent to which the expansion of higher education in the United States impacted indigenous peoples residing on land claimed by the American government. Thirty-seven colleges and universities in the United States (US) memorialized their indigenous history by dedicating their entire institution to the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC) and becoming a Tribal College and University (TCU) (American Indian Higher Education Consortium). Although only 37 of 2,618 accredited colleges and universities in the United States are TCUs, many institutions still honor their indigenous history by erecting monuments, small and large, memorializing their indigenous predecessors’ great sacrifice of their lands (University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education). Monuments among college campuses range from dedicated buildings, murals, plaques, and statues, among others. These monuments often result from what Christa Olson likes to think of as the power dynamics of political and cultural boundaries and maintains that the dynamic shapes rhetorical practices and representations (Olson). In the case of this exhibit, the power dynamic exists between university officials and Indigenous history, resulting in memorials warranting rhetorical analysis. This digital exhibit will argue that these landmarks emphasize colleges’ willingness to honor indigenous peoples and embody the colleges’ commitments to diversity and awareness of indigenous heritage by analyzing two American universities’ indigenous memorials in contrast to a Canadian university’s memorial.

Student-Influenced American Memorials

The University of Missouri acts as a recent example of a non-TCU in the United States (US) attempting to honor the Native Peoples among the student body and of the university’s historic land. In the 1800s, the Morrill Land Grant Act allowed states in the US to allocate federal funding for the establishment of public colleges and universities west of the Mississippi River. Of the 112 land-grant institutions created from the Act, one would become what is now known as the University of Missouri which received land acquired from the native Osage People (Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group). The US government negotiated two treaties, one in 1808 and another in 1825, with the Osage for their land. However, due to poor communication between the government and the Natives, the Osage unintentionally gave up all the rights to their land. Ultimately, the Osage relocated to a small county in Oklahoma against their will, losing not only their land but also a part of their history. To honor the Indigenous Peoples of Missouri, the Osage whose land is now a part of the University of Missouri (Mizzou), and Native Peoples attending Mizzou, a student-led organization, called Four Directions, set out to erect a commemorative mural. In collaboration with the Missouri Student Unions and the College of Arts and Sciences at Mizzou, Four Directions raised the funding and support to bring Yatika Starr Fields, an Osage/Cherokee/Creek artist, to the University to paint the mural. Completed in April 2020, 181 years after Mizzou’s founding, the mural represents the re-establishment of Native Peoples on campus, a shift towards an inclusive, restorative, and forthcoming school, and Mizzou’s connection to its unique land history and connections to the Osage people. Displayed prominently in the schools’ Student Union, this memorial’s vibrant colors and unique graphics capture the positive, proud spirit of Mizzou’s indigenous community. The choice of the university to select a mural designed by Yatika, a Native Osage, represents their goals of launching a more inclusive era of the school, in terms of recognizing Native heritage, beginning with a powerful mural that reaches every student walking the halls of the Union.

In contrast to the University of Missouri’s exotic memorial to their Indigenous Osage Peoples, Columbia University reluctantly honors their indigenous predecessors in a small memorial on campus. Whereas the University of Missouri originated from the Morrill Land Act in the 1800s, Columbia University originated because of an English royal charter in 1754 (Columbia University). With little governance and protocol for establishing colleges, Columbia’s founders ignored the fact that the Lenape People resided on the land before British colonization. This trend continued and by the 21st century, still, no formal recognition of the campus’s indigeneity existed anywhere. In 2012, the student-run Native American Council at Columbia University created a petition through Change.Org to prevent any further erasure of the campus’s Indigenous Peoples. In 2016, 262 years after the University’s opening, Columbia’s leaders erected the Lenape Plaque to memorialize the Lenape People and formally recognize their presence in the past and present histories of Columbia’s campus. Not only does the plaque represent an official acknowledgment that a Native history of Columbia University exists, but also represents the immense pride felt by Indigenous Lenape student for their heritage. The plaque was a product of student activism and embodies students’ efforts to transport history across time and space to acknowledge both the past and present impact of Indigenous Peoples on higher education in some of the first leading American universities. The plaque’s dull colors and heavy text reflect the reluctance of university leaders to erect a memorial while simultaneously representing how students have the power to influence institutional leaders, even though the outcome was a small, bleak plaque generally obscured from the heart of Columbia’s campus.

Administration-Influenced Canadian Memorial

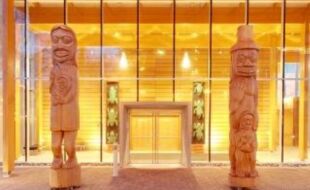

As evidenced thus far, American colleges and universities have a history of recognizing Indigenous Peoples and their communities’ Native histories only because of student activism. University leaders played little and somewhat reluctant roles in aiding their students’ goals for honoring indigeneity. The University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada offers a unique take on how university leaders can take the lead in not only honoring their Indigenous Peoples but also recognizing present students’ heritage and providing them with a safe space on campus. The Coast and Straits Salish Peoples resided on the land of what would later become The University of Victoria in British Columbia. In 2007, the University adopted a strategic plan to create a vision for the future based on the ideals of building strength among the campus and surrounding communities of Indigenous students and Peoples. After intense collaboration between the University’s President, Dr. David Turpin, and the Chiefs and Elders of the Coast and Straits Salish and the Saanich, Alfred Waugh, a First Nations architect, created the welcoming design of the First Peoples House. With a community-centered layout and design incorporating Salish artifacts, longhouse-like red cedar planks, and a timber canopy, the building reflects the traditional architectural influences and contemporary values of British Columbia’s Indigenous Peoples. It also acts as a “home-away-from-home” for the University’s indigenous students and memorializes the traditions and teachings of the Indigenous tribes in the surrounding areas. To reflect these values, all people entering the building must walk in with a humble heart and a pure mind. Unlike the meager student-influenced memorials common in American universities, the University of Victoria provides a grand memorial to indigeneity that provides not only a viewing experience, like the two American memorials, but also a physical and cultural experience by entering the building and surrounding oneself with a positive group of students, staff, faculty, and residents all dedicated to honoring culture. American colleges and universities should look towards schools, like the University of Victoria, that visually, physically, and spiritually memorialize their history by providing their campus and students with more than a piece of art or a plaque.

References:

American Indian Higher Education Consortium. “Tribal Colleges: Educating, Engaging, Innovating, Sustaining, Honoring.” Who We Are, www.aihec.org/who-we-are/index.htm.

Columbia University. “History.” Columbia University in the City of New York History, www.columbia.edu/content/history.

Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group. “Map of Land Grant Universities.” Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group Resources, 23 Mar. 2017, nesawg.org/resources/map-land-grant-universities.

Olson, Christa J. Constitutive Visions: Indigeneity and Commonplaces of National Identity in Republican Ecuador. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014.

University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. “How Many Colleges Are in the US? Numbers of Colleges and Educational Institutions.” Urban Education Journal, www.urbanedjournal.org/education/how-many-colleges-are-in-the-us-numbers....