Acknowledging the Forgotten History: US, Australian, Japanese conceptions of Indigeneity

Introduction

Most people assume that the history and culture of indigenous people have been lost and forgotten. However, these monuments show that in today’s society, there is an attempt to acknowledge the history and culture of indigenous groups that were once ignored. And in this digital exhibit, I will argue that memorials recognize the injustices that indigenous faced in the past by paying homage to their culture. This exhibit will explore the monuments dedicated to the Aboriginal Indigenous people of Australia, the indigenous clans that fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn, as well as the Ainu people of Japan. Even though located in different regions, these indigenous groups relate in that they were victims of domination and forgotten by most of society until memorials were built to acknowledge their history.

Indian Memorial

The first memorial is located in the US on the battlegrounds of Little Bighorn. The Battle of Little Bighorn was between the US army and indigenous clans which included the Lakota and Northern Sioux (Urwin). The battle was fought in the attempts to push the Native Americans out of their land in order to reach gold, however, this battle did not work in favor of the US was they lost the battle as well as the causalities caused on both sides (Urwin). However, the initial memorial for the battle is a poor example of how to represent indigenous people and their history. The battleground was given the name National Cemetery of Custer's Battle-Field Reservation and only headstones were given to fallen American troops (Indian Memorial). The reservation disregards the lives of the indigenous people that were lost during the battle to protect their land.

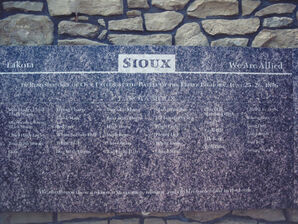

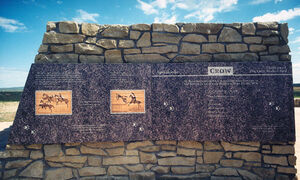

However, in an attempt to address the lack of representation and acknowledgment of the indigenous lives lost, the US Congress introduced the Indian Memorial addition to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1991 (Indian Memorial). The memorial is made up of several plaques that are dedicated to each clan that fought in the battle as well as a centerpiece called the Spirit Warrior Sculpture. The plaques recognize the lives of the indigenous people that were lost during the battle. Each indigenous person who died had their name engraved in the plaque corresponding to their clan. This is a method in which the artist of the memorial attempts to recognize the lives of the indigenous people that were lost during the years after the battle. Furthermore, the Spirit Warrior Sculpture is the main piece that is made of steel and shaped to represent the warriors of the indigenous clans riding on horses into battle. To help support the idea of how indigenous people are memorialized, Barthes' argument of how images have a connotation and denotation can be used. Barthes' argues that the connotation of an image can be identified through understanding the culture in which the image targets (Barthes, 162). In this memorial, the denotation of this sculpture is to represent indigenous warriors riding into battle. However, the connotation of the sculpture is to highlight the bravery and the clan's culture through the traditional armor, weapons, and willingness to fight even though they are thought to not win.

By adding the memorial, it helps to concrete the history of the indigenous people that were once ignored. Before the memorial, the only way that the story of the indigenous warriors that fought in the battle was passed down through oral tradition, but with a memorial that acknowledges the lives as well as bravery that the warriors held, their history is set in time and respected.

The Aboriginal Memorial

The Aboriginal Memorial was made in order to commemorate the indigenous groups in Australia who lost their lives defending their land since the year 1788 (The Aboriginal Memorial Introduction). The Aboriginal people of Australia struggled with oppression and violence from the British empire such as the introduction of disease, massacres, and disruption in their land which all lead to the devastation of the population (The National Archives, British Empire). This memorial was constructed in 1987 which marks the 200 years in which colonialism began by the British. Through this memorial, the artists attempt to incorporate and honor the culture of the indigenous people as well as commemorate the lives lost.

This monument is constructed of 200 hollow log coffins to represent the length in which the Australian indigenous people struggled under the British empire. Each log is one year for which the British fought with the Aboriginals. Furthermore, the artist attempts to incorporate the culture of the Aboriginals is through the layout of the memorial. The memorial is strategically mapped out so that the logs are map out the Glyde River. This is done to represent the ritual called Dupun Ceremony is done to ensure the safe passage of the soul to the afterlife (The Aboriginal Memorial Introduction). The Dupun Ceremony is a burial ritual done by the Aboriginals in which the bones of the deceased are placed in hollow log coffins, hence the inspiration for the use of hollow logs in this memorial (The Aboriginal Memorial Introduction). The log coffins not only represent the number of years of colonialism, but also the lives that were lost during the 200 years of colonialism. Another method that the artist used to honor the lives of those lost to the British is the paintings on the log coffins. The log coffins in the memorial are painted with traditional clan designs known as "dreamings" which is described to be the religion that the indigenous people followed that is based on their ancestors (The Aboriginal Memorial Introduction). Through these visual techniques, the artist encompasses Barthes' argument of how images can be understood through a second language by understanding the culture of the topic (Barthes). In this memorial, the denotation to is seeing several sticks emerging from the floor with a walkway laid out. However, by understanding the history of the Aboriginal people's history, the reader is able to understand the materials and structure alludes to the Aboriginal people's heritage such as the Dupun Ceremony.

Kamui Mintara

Kamui Mintara (Playground of the Gods) is a monument dedicated to the Ainu people of Japan. The Ainu culture was almost erased completely by Mainland Japan after the Ainu people lost the Menashi-Kunashir Rebellion, resulting in the Japanese taking control of the Ainu people's land (Afshar). The Ainu people were forced to assimilate into Japanese culture after the Japanese passed the Hokkaido Aborigine Protection Act in 1899 which lasted till 1997 (Afshar). Their culture and language were almost wiped out, however, an attempt was made by Toko Nuburi to acknowledge the lost culture through the production of the Kamui Mintara memorial in 1990 (SamR). The year that the memorial was constructed was done to celebrate the 25th anniversary between two sister cities in Hokkaido as well as an attempt to keep the dying culture alive (SamR).

The Kamui Mintara memorial attempts to recognize the Ainu culture alive as it is a representation of their beliefs. The totem poles that make up the monument have engravings of animals such as bears, owls, and fish on the top of the poll. It is possible to use Barthe's argument again with this memorial in the way the totem poles are constructed in order to recognize the Ainu culture. At first glance, the totem polls seem decorative with the animals at the top, however, the connotation of engraving the animals is to represent the belief that the Ainu people practice. The Ainu people believe in the idea that the animals are Gods that create the physical world which is demonstrated through the tall totem polls to represent the Gods descending into the physical world to build it (Ashfar). Furthermore, there are shorter totem polls than the ones with animal carvings to demonstrate the friendship between the two sister cities as they are located in the physical world (Ashfar). To further support how this memorial pays tribute to the Ainu people is through identifying the power in the memorial as Gries says

"if visual things have a power of their own not only to move but also to influence human thought and action." (Gries, 59).

In this memorial, the totem poles hold power because of the unity in the way the poles are constructed as well as the close proximity that they stand. By understanding that this memorial is dedicated to the Ainu, it represents them as a strong group of indigenous people who stand together even though they have faced oppression. This memorial tells the story that their culture will not be forgotten now that it is built and the Ainu people stand united to ensure their traditions do not vanish.

Works Cited

Afshar, Dave. “A Tribe Dispossessed: How Japan Is Losing Its Ainu History.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip, 4 Apr. 2017, https://theculturetrip.com/asia/japan/articles/a-tribe-dispossessed-how-...

Barthes, Roland. Rhetoric of the Image. 1977.

“Indian Memorial.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/indian-memorial.htm.

Gries, Laurie E. Still Life with Rhetoric: a New Materialist Approach for Visual Rhetorics. Utah State University Press, 2015.

SamR. “Playground of the Gods.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 7 Dec. 2015, www.atlasobscura.com/places/playground-of-the-gods.

Simpson, Hayley. “The Surprising History Behind Canada's Playground of the Gods.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip, 20 July 2017, https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/canada/articles/the-surprising-...

“The Aboriginal Memorial Introduction.” The Aboriginal Memorial, National Gallery Of Australia, https://nga.gov.au/aboriginalmemorial/home.cfm

“The National Archives, British Empire.” The National Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/empire/g2/cs2/background.htm.

Urwin, Gregory J.W. “Battle of the Little Bighorn.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 18 June 2020, www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-the-Little-Bighorn.