Commemorating the Past and Reflecting on the Present

Introduction

Mourning for those who fell to a tragic event is one of the most natural instincts that every human share. Standing tall after a tragedy and maintaining unity can only be achieved through dealing with the scars that the aforementioned tragic event has caused, which leads people to express their emotions in order to protect those around them from spiraling down in a cycle of sorrow. This is exactly what memorials are built around to globe. Memorials, or rather monuments that cherish a group of people, can be utilized as tools for people to deal with mourning in a healthy way, yet this ritual of dedicating memorials to the people of the past is not immune to provocative criticism, regardless of the sentimental values that are associated with them. Although both scholars and the general public choose not to question the essential purpose of the memorials dedicated to the indigenous people around the world due to the possible malice that might arise as a natural by-product of criticizing those who have already suffered enough in the past, in this exhibit I argue that a simpler yet better alternative is available for us to cherish those who have been slaughtered in the past. Instead of assigning such sentimentalism to monuments that do not necessarily reflect on the lives which the memorial was dedicated to in the first place, we should seek to create memorials that will benefit the living and make them harbor love to the ones that the memorial was dedicated to, rather than bland sculptures that will allow the horrible past overshadow the joy of life.

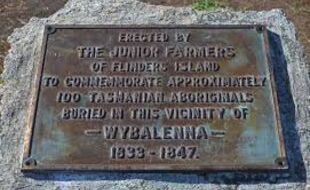

In an attempt to console those who feel terrible about the mass murder of the aboriginal people in Australia, many have erected various memorials. These memorials were indeed built by sincere empathy, yet it is debatable whether if they have an impact on the lives who are still being affected by the consequences that trickle down from the very beginning of colonization. The aboriginal burial site, for example, was built as a result of the initiative that the local farmers took, yet the mere impact of a burial that is dedicated to those who don’t bear a name on their graves, let along anything that marks their graves, is almost certainly ignorable. Arguing against the significance of such memorials prompts another trouble that, perhaps, has to be dealt with even sooner. Are we doing enough for the victims who are alive today?

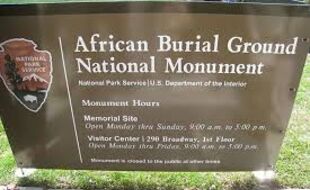

This is another example of dedicating a symbolic gravestone to the people who were killed and were not able to leave a legacy behind. Though this monument was dedicated to the Africans who were not necessarily indigenous to the Americas, it is still important to note that the sincerity that allowed this monument to be built was essentially the same as the Aboriginal Burial Site. In contrast to the monument in Emita, this monument has a considerably more active role in regard to the efforts against the consequences of the tragic past of the indigenous people of the world. In other words, the African Burial Ground Monument is a more engaging memorial compared to the Aboriginal Burial Site, simply because of its location. The fact that this monument was erected in the center of New York City makes a difference when it comes to raising awareness for those who were impacted by the colonizers and allows the dullness felt by these indigenous people to be shared with a larger audience. In the end, however, this structure is nothing more than a passive message and fails to acknowledge the obstacles that the indigenous people of today face.

Coronado National Memorial Park, in my opinion, is by far the most impressive piece of this exhibit. This park was dedicated to the indigenous people of North America, and it does a great job of recognizing the legacy that was left behind those who were killed as a result of the aggressive policies that were implemented by the US government at the time. Dedicating a piece of nature and maintaining it with a feeling of respect to those who were fallen surely fulfills a memorial’s duty to commemorate those who are the subject of it. Moreover, as opposed to the first monuments in this exhibit, this park has an active role in today’s society and goes beyond the expectations of a memorial. It is an undeniable fact that national parks are essential to preserving the very nature that Native Americans tried to preserve at the cost of their lives. In the end, memorials dedicated to indigenous people should not only be seen as simple tools to commemorate a group of people, but also consolidate the legacy of those who were sacrificed in the past.

References

“African Burial Ground National Monument (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/afbg/index.htm.

“Coronado National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/coro/index.htm.

Design, UBC Web. “Aboriginal Burial Site.” Aboriginal Burial Site | Monument Australia, monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/culture/indigenous/display/71004-aboriginal-burial-site.