Keeping Greek Tradition Alive: The Power of Monuments in Communities

A Monument Is Worth A Thousand Words

History is fluid amongst our present world by the means of the individuals who care to keep it alive but more specifically through the representation of history in the community, like the presence of physical representations. Monuments, of which “can take many forms, including sculpture, fountains and even murals” (Burling), are a token of history presented throughout the world that serve as a visible representation of their subject in their respected location. Marking their territory in the future, those physical representations serve as a constant reminder of the history they represent, however, not all history is expressed physically and that doesn’t mean that the history is lost. Stories serve as a way of honoring and spreading history of the past, but without a tangible delineations narratives and history can get lost and their importance as serving as an emblem or an honor to the people it belongs to dwindles. The Greek communities of America serve as a great example to showcase the importance of showcasing history through physical means. Having a physical monument placed to honor or represent a group of people and their history is more meaningful and expresses a greater power in withstanding as a piece of unchangeable history rather than a word by mouth legend of the people that came before the current community.

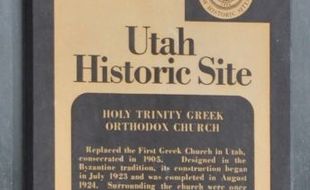

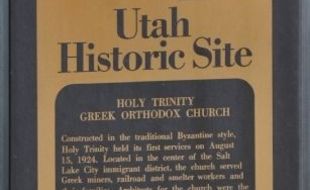

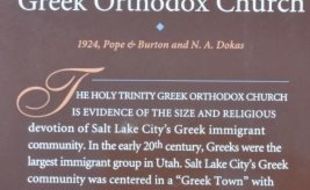

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church Memorials - Salt Lake City, Utah

"It's (all) Greek To Me"

To express the significance of my argument, I will relate it to the representation of Greek communities through the presence of Greek Orthodox churches in the United States. Within the posted memorials, the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Salt Lake City, Utah is one of the biggest Greek churches of western United States. As listen on the church’s memorial plaque, the “Greeks were the largest immigrant group in Utah”. Data provided by the US Census, immigrant population in the West increased by over 600% during the 1860s (Gibson). This was due to the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad that was finished in 1869, allowing immigrants from the East (mostly Europeans) to travel westward in search for jobs. As many immigrant groups, Greek immigrants were used as cheap labor to construct railroads in the Midwest (Papanikolas). Looking for a place to escape discrimination upon the completion of the railroad in Utah, Greek immigrants found Salt Lake City. In 1905, the first Greek church was built in Utah. By 1924, the Greeks rebuilt the church near downtown Salt Lake City, an area of which became to be called “Greek Town”. Physical memorial plaques located around the church state that “The church remains a symbol of early Greek life in Utah” and that “Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church is evidence of the size and religious devotion of Salt Lake City's Greek immigrant community”.

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral Greek School - New Orleans, Louisiana

A Tale Once Told

Upon a conversation with a Greek Orthodox priest of over 60 years, the presence of Greek Orthodox Churches dates back to before the creation of Salt Lake City’s church. Father Theodore mentioned that the oldest Greek church he knew of was in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he served as a visiting priest for a few years. After a quick Google search, a handful of websites claim that the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral in New Orleans is the first established and recognized Greek church in the United States. From the church’s website, the first Greek church was built in “1866 as confirmed by news reports and the sale document of the property” (Holy Trinity). Asking Father Theodore if he had any current contacts with the church to confirm a few inquiries, he mentioned to me that he knew of a few people that might help me. He contacted the church’s council to inquire on my behalf regarding any monuments set by the government or donated by the community that state outside the church that it was the very first one of its kind in the United States. A member of the council informed him that there wasn’t any plaque that stated the foundation of the church, but the people of the Greek community know that it was the first church (based on what was always known throughout the generations of the congregants) and it could be proven by saved documentation (as listed on their website). To an outsider and someone not involved with the Greek church, New Orleans’ cathedral is just another church, but to the Greek community serves as a historic and operating monument of the history of Greek Orthodoxy in the United States. Without a way to physically depict the church as a historic site, the identity of the church is lessened amongst the majority of the people of New Orleans. The lack of a memorial tag makes it so visitors or people of the community will not grasp the importance of the church amongst Greek-Americans.

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral - New Orleans, Louisiana

Remembrance By The Senses

The presence of a physical monument does not only serve as a unchanging honoring of the people it represents but “monuments and memorials do what no documents or records can. They engage the population in maintaining memory on a daily basis” (Burling), something that is very prominent within the Greek communities across America. Memorials can create a memory in someone in a stronger scale if its tactical, thus allowing that remembrance to last longer within the culture and the minds of the people as shown with the Greek church in New Orleans. “Memorials shift in meaning as generations change. Time alters understanding and blurs memory; architecture remains” (Ivy). Memorials and monuments do not only help us maintain the memory of significant history to be expressed in the present time but also “public memorials are preserved for the future… to help [people] to remember and prevent changing historical facts and events” (Gurler). By having physical monuments rather than stories or verbal customs passed down by generations, we are able to preserve parts of history for generations to come. Memorials take memory a step further by taking a memory or legend and visualizing it for the world in a universal language of art expression, plaques with descriptions or dedicated areas to remind people of the past and relate the importance of history to future generations.

Works Cited

Burling, Elizabeth J., "Policy Strategies for Monuments and Memorials". Theses (Historic Preservation). University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons, Jan 2005, http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/21

Gibson, Campbell, and Emily Lennon. “Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-1990.” Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 21 May 2012, 05:04:47 PM, www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/twps0029.html.

Gurler, Ebru Erbas, and Basak Ozer. “The Effects of Public Memorials on Social Memory and Urban Identity.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 82, 3 July 2013, pp. 858–863., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.361

“History.” Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral, New Orleans Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral - IatroDesign, LLC, www.holytrinitycathedral.org/index.html.

Ivy, Robert. “Memorials, Monuments and Meaning.” Architectural Record, vol. 190, no. 7, July 2002, p. 84 – 87.

Papanikolas, Helen. “THE GREEKS IN UTAH.” Utah History Encyclopedia, Utah Education Network - UEN, www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/g/GREEKS_IN_UTAH.shtml.