Forgetting a Past of Forgotten Migrations: The History of the Slave Trade in North Carolina

Introduction

North Carolina has one of the nation’s oldest and most thorough highway marker programs in the nation. Since 1935, over 1,600 plaques have been created, lining highways across the state and memorializing historical figures and events for all those who pass by (North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources). Despite this abundance of plaques, there is a group that lacks representation. North Carolina had a significant role in the slave trade, yet a concerning lack of attention has been given to the accurate memorialization of those often excluded from dominant representations of history in state memorialization programs. The failure to acknowledge these groups exemplifies the state’s denial of responsibility, alluding to what Charles Mills and Linda Alcoff have called ‘an epistemology of ignorance.’ By assuming this facade, Mills and Alcoff point out, “Western publics come to believe not only that the world is post-colonial and post-racial, but also that the long history of colonialism, racialised indentured servitude, indigenous genocide, and transatlantic slavery have left no traces in culture, language, and knowledge production” (Danewid, 1681). North Carolina’s limited representation of the slave trade on historical highway markers demonstrates its desire to forget a past tainted by slavery.

North Carolina's Background in the Slave Trade

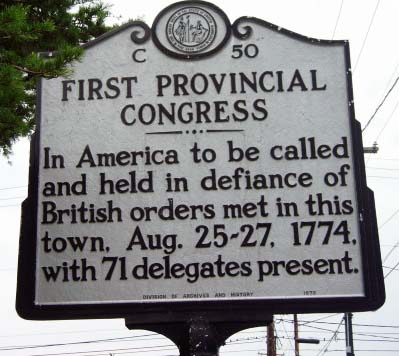

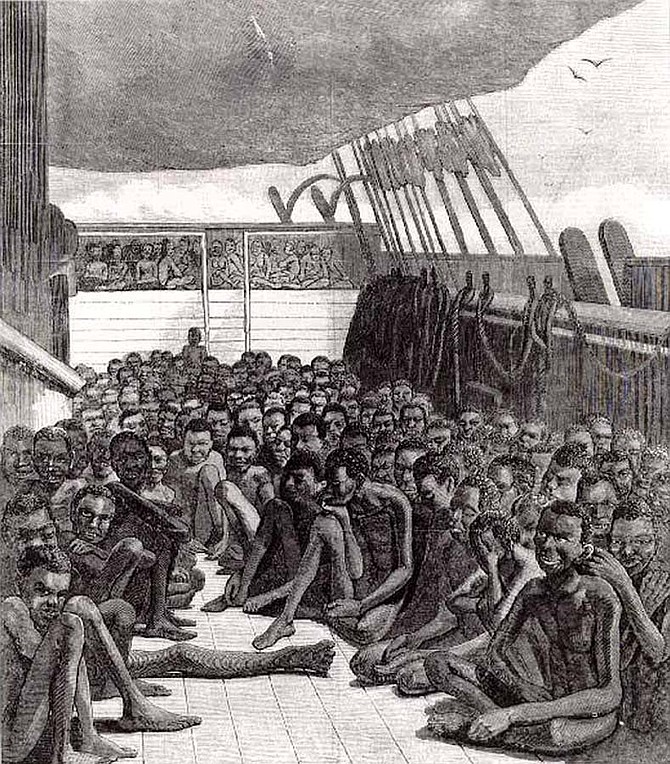

In the late 1600s, numerous African slaves were directly imported into the Carolina colony from Guinea (Crow). Although North Carolina’s importation paled in comparison to many other southern colonies, the slave trade is an irrevocable part of the state’s history. As such, it is crucial that efforts be made to address the past in order to come to terms with racial identities and narratives today. Wilmington was a dominant port used to deliver slaves to the Lower Cape Fear region (Crow). Due to the state’s thriving agricultural market, slave labor was in high demand. By 1860, 19 counties in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont counted black majorities (Crow). Despite this, attempts to reduce or prohibit slave imports were made as early as August 1774 when the Provincial Congress in New Bern resolved, "We will not import any slave or slaves, or purchase any slave or slaves, imported or brought into this Province by others, from any part of the world, after the first day of November next" (First provincial, anchor). However, the importation and selling of slaves continued, despite actions taken by the government.

A Desire To Forget

Mentions of Slavery

The North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program portrays a narrow and celebratory view of local and national history, leaving little room to shed light on the stories of minority groups. Mentions of slavery often appear under the descriptions provided for influential, white men, such as that of John Gray Blount. In 1987, The North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program cast a plaque in honor of Blount at the location of his home (North Carolina Office of Archives & History, "John"). The plaque commemorates him as a merchant and land speculator who had shipping interests across the state. The online database provides further information, noting him as an individual whose family had significant influence over the political and economic endeavors of the state. He and his business partners “ owned sawmills, gristmills, tanneries, and cotton gins, and engaged in agricultural pursuits and the slave trade” (North Carolina Office of Archives & History). This marker appears as one of the four results containing the term “slave trade” when searched in the database. Rather than acknowledging the stories of those who endured the horrors of slavery, the program chose to commemorate someone who helped to facilitate its exploitations; his role in the slave trade is mentioned as merely an afterthought. Many plaques commemorate slave-owning white men, broadcasting their achievements rather than their pitfalls.

Detached and Dehumanizing

Broadened Recognition

Despite an overwhelming lack of representation throughout historical markers in North Carolina, efforts have been made to accurately reflect different perspectives of history. Plaques have been made to celebrate the achievements of influential slaves and African-Americans such as educator and feminist Anna J. Cooper or fugitive slave, writer, and abolitionist Harriet Jacobs. Nonetheless, these markers celebrate achievements rather than acknowledging painful and discriminatory events in North Carolina’s past. Additionally, there is no acknowledgement of North Carolina’s role in the direct importation of slaves to Carolina colony. In order to work towards a more nuanced, collective history, we must first return to where the roots were first planted on the coast.

Conclusion

History is all around you whether you realize it or not. From monuments to battlefields, every location has a story. By preserving the stories of the past and marking the paths of our ancestors, one makes the assertion that the narratives of our nation matter. Historian Mary Tyler-McGraw describes public monuments as a crucial fixture to civic education and to control them is to control the meaning of local history, dictating whose stories belong in local narratives (Horton and Horton, 157). Governments have great say in how groups and events are portrayed, dictating whose stories are remembered and whose are forgotten. When it comes to North Carolina's "history-on-a-stick" method of quick, condensed history, every word matters. Although these plaques reinforce traditional historical narratives, celebrating the migrations of pilgrims and westward-bound settlers, it is time that the fading history of the slave trade in North Carolina is memorialized.

Citations

Crow, Jeffrey J. “Slavery.” NCPedia, University of North Carolina Press, 2006, https://www.ncpedia.org/slavery.

Danewid, Ida. “White Innocence in the Black Mediterranean: Hospitality and the Erasure of History.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 7, 2017, pp. 1674–89, doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1331123 .

Horton, James Oliver, and Lois E Horton, editors. “Southern Comfort Levels: Race, Heritage Tourism, and the Civil War in Richmond.” Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory, by Mary Tyler-McGraw, Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2009, pp. 151–167.

Horton, James Oliver, and Johanna C. Kardaux. “Slavery and the Contest for National Heritage in the United States and the Netherlands.” American Studies International, vol. 42, no. 2/3, June 2004, pp. 51–74.

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. “Highway Markers Program.” North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/highway-markers-program.

North Carolina Office of Archives & History. “James Wellborn 1767-1854” North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Office of Archives & History — Department of Cultural Resources, https://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=M-42

North Carolina Office of Archives & History. “John Gray Blount 1752-1833.” North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program, North Carolina Office of Archives & History — Department of Cultural Resources, www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=B-51.

“The First Provincial Congress.” Anchor, the Government and Heritage Library, https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/first-provincial-congress.