Idealization vs Realism in West Virginia Coal Mining Accident Memorials

Memorials to coal mining disasters in West Virginia that involved the deaths of many European immigrants (from Italy, Poland, and Greece) often place the fact that many of the dead were immigrants in a prominent position. Some of these monuments were created in the 1900s, and some were created in the late 2000s, a time when coal mining was beginning to lose favor. The three selected memorials show that many communities in West Virginia had in the past glorified those people who worked in coal mining (even against the advice of immigration officials) and create an idealistic portrayal of coal mining. It will also show that public opinion in West Virginia seemed to be changing to a more realistic portrayal, even as portrayals from outsiders stayed idealistic.

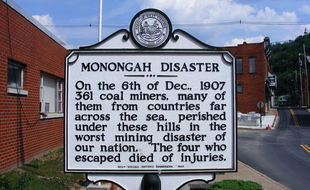

The official black and white plaque erected by West Virginia about the Monongah Disaster in the 1960s speaks in more dramatic language which takes up space. “On the 6th of Dec. 1907” and “from countries far across the sea” are glorifying and honorific phrasings, but they take up much more of the limited space than “6 Dec. 1907” and “immigrants” would have taken. The plaque notes as concrete facts only the date and the numbers of miners who died. It gives some details about where they died (whether they escaped or not), but does not discuss the reasons for death or what was or could have been done to prevent future such incidents. The portrayal of the workers as immigrants is done in a picturesque way, and the portrayal takes up much of the space on the plaque.

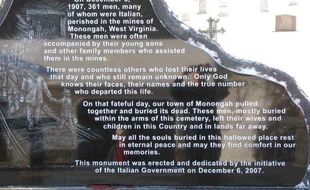

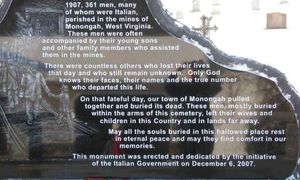

In much the same vein, the monument put up in 2007 by the Italian government for the Italian immigrants who died in the Monongah mining disaster. The voice in which the monument is written has flowing, dramatic language and portrayals, but it glosses over issues such as child labor (which is actually pictured in a drawing on the memorial) without mentioning the clear negatives of this. The drawing is not shown as unhappy, and the memorial claims it seeks to offer “comfort” to the miners by representing that those alive still remember them. The memorial says that the mine claimed the lives of countless others, but is blameless on this issue, redirecting any anger that may arise to trust in a diety. The immigrants are portrayed as an important part of the culture of the town and the mine, having children and families within the community. Again it is picturesque, taking up space that might have been used to discuss mistakes made or how such an accident could be prevented from happening again. The shape of the memorial is that of a large lump of coal, done in black stone to further the illusion. The memorial as a whole heavily reflects the sentiment of how the people of West Virginia chose to portray the disaster nearly fifty years previously. People in West Virginia, however, did not necessarily still maintain that sentiment. Many more mine disasters had happened since, and the coal mining industry was beginning to die off.

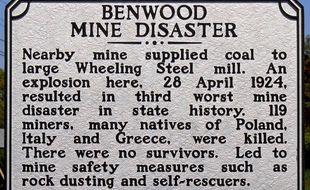

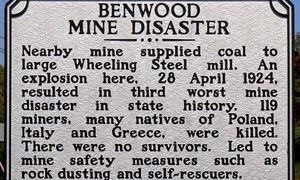

A 2007 memorial put in place for the Benwood mine disaster is also a black and white plaque, but it is notably different from the Monongah 1960s plaque. The font is smaller and the text is given in direct wording that attempts to give as much specific information as possible. Readers are told about the role of the mine, the countries immigrants were from, and the safety measures that were developed after the disaster. There is little to no glorifying or idealized language when referring to either immigrants or natives.

This analysis suggests that West Virginian communities were changing their opinions on coal mining as the industry began to die off. Rather than focusing on more glorified ideals and picturesque language, memorials began to focus on facts, situations, and safety improvements. As the 2016 election results showed, many West Virginians still hoped for the return of the coal industry even years after 2007, but the changing style of memorials suggest that they hoped for a renovation of the coal industry as well. A renovation that would make the mines safer and more accountable, so that both natives and those “from countries far across the sea” could live to make their mark on society, rather than leaving their mark in the form of a black and white plaque beside the road.