Durham, a southern melting pot success?

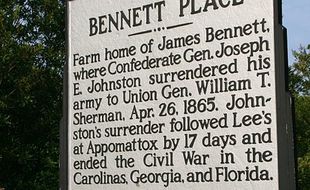

Bennett Place marks the first, large demographic shift in the Durham area. Many might recognize it as the place where the largest Confederate surrender of troops was negotiated, but to the Durham area this monument stands for more than just what’s on the surface. As both armies sat around for weeks during the surrender process, many of the soldiers gained a taste for the local tobacco and cigarettes. This led to a boom in Durham tobacco industry after the war. It began Durham’s transition from a rural area identified only by its railroad station to an urban center. With this growth of Durham city we saw people move in from the surrounding countryside, rural whites and newly freed blacks, to look for new opportunities in the city. This change is so deeply rooted in Durham’s history that even today you can see the remains of old tobacco warehouses crisscrossing the landscape and antiquated ads for brands such as Lucky Strike painted on some of Durham’s most famous landmarks. However going to Bennett’s place you would never guess its impact on the rest of the region. The importance of the events that took place there are put strictly into a national context and the local effects of such a historic event are left almost completely out. Possibly it is its status as a “State Historic Site” that blinds it to talking about the local scene or possibly they do not want to credit Durham’s rise to the tobacco industry, maybe they want that controversial part of Durham’s past simply swept under the rug and left there - a big unsaid truth.

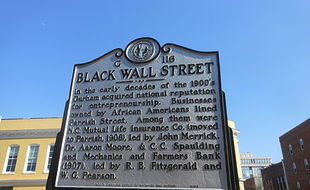

The tobacco industry may have given rise to urban Durham but is black life that defined it. In downtown Durham on the 400 block of Parish street one can find a sign memorializing “Black Wall Street”. As early as the late 19th century this block in the heart of Durham became a hub for black businesses and investment in the area. Spearheaded by John Merrick and his Mutual Life insurance company, what it meant to be a black businessman was shaped by the people who worked on black wall street. Due to the success of these businesses downtown Durham became a hub for Black culture and life. Families moved into the area (causing of course a case of “white flight”) and claimed it for their own opening up stores and businesses. Much of what gives Durham the unique presence it has today is the prevalence of the Black community in the area established due to Black Wall Street. They established a trend of progressivism that was held through the Civil Rights movement (where Durham was the site of the first sit-in protest) and carries to today where Black Art events aim to empower the community and continue to lift up problems of racism and diversity. However, there is a discrepancy in how Black Wall Street is presented and the streets around it. Gone are most of the historically black businesses. Gone is the housing that families lived in for generations. Gone is any sense of what the street even unless you read the sign or look closely at the preserved structures of a couple of the historic buildings. Black Wall Street is no longer the center of black life in Durham. Why? And why does it get only a small plaque in remembrance. A sign easily miss-able or dismissible in the bustle of the city.

Perhaps one of the most iconic statues in Durham is that of “Major” the Durham Bull. With a 4.8-star Google review and unfortunately pronounced and “buffed” testicles, “Major” stands proudly in the middle of the downtown area. He is a symbol of Durham’s unity as a city even as the city’s reputation plummeted in the 90s due to high crime rates and a number of other problems people associate with “inner city” life. However, that’s not when the Bull was built. The Bull was built in 2004 at the beginning of what would possibly be Durham’s most controversial migration: the gentrification of downtown Durham. After the reworking of the American Tobacco district, downtown Durham became a hotspot for tech companies and people who wanted to live close to the research triangle area for cheap. Young, mostly white families moved into the downtown area fixing up houses with large paychecks and creating a large demand for the boom in Durham apartments. Suddenly you could not walk two feet without seeing a crane. And who was getting kicked out of this suddenly-prime real estate? Low income families who had lived there for generations. I new highway was built cutting off the poorer (and largely minority) communities from the downtown area and rent prices skyrocketed forcing families to leave or be evicted. But what did the majority of people see? The Durham bull standing strong. The Durham Bull saying “this is for the best. Look at our thriving downtown. Look at our bustling urban center, our new microbrewery scene, our new high-rise apartments”. Yes Durham stood strong and became a thriving center of urban life. But what was the cost? Major certainly isn’t spilling the beans. And the sign for Black Wall Street might as well be hidden behind a wall for all the attention it gets now that there is a new shiny bronze bull in town.

There is one more migration to mention for Durham. Over the past decade or so the Hispanic population has boomed in the area. Gentrification for all its done has in fact created a huge number of jobs in the construction industry. It would be hard to imagine a building in Durham ever getting built today without the large Hispanic population. According to Latino Life in Durham, by 2010, 14% of the population identified as Hispanic/Latino. Yet, there is not a single monument dedicated to them unless you count the numerable buildings built with the sweat of their work in the name of a gentrified Durham landscape. And they aren’t alone in their struggle to be recognized by durham monuments. Each of the monuments I’ve talked about here barely talks about the actual people who were affected by the changes they represent. Bennett Place ignores the local impacts of the civil war, Black Wall Street barely mentions the larger black community who moved into the downtown area (focusing instead on the story of the businesses and their economic impact) and “Major” literally faces away from the freeway (yes, the one that cuts of downtown from low income communities he literally has is back on the people who lived where he now stands). What do these monuments say about Durham. They suggest an area that has put prosperity above its people and now that prosperity has been achieved has turned their back on the people who were needed to make it happen.

I do not want people to get the idea that I hate Durham or that they should hate Durham. There is simply a disparity that needs to be fixed in how Durham views its history with an honest mind. We simply cannot just praise ourselves with a pat on the back at our great town without honestly looking at how we got here. We need to show our history with truth and equity. We need to think critically about the monument we have in our city and how they show a story to others. We need to see how these monuments display biases and work to fix them. Recently a confederate statue was pulled down from where it stood outside the old Durham Courthouse. This is a start but doesn’t go far enough in examining even monuments that we hold most dear to see the effect they have on how we display the past and indeed the current landscape of Durham.

Durham has a long history of migration that has spanned many groups over many decades. Blacks, whites, and Hispanics have migrated to Durham in large waves reaching back as far as the end of the Civil War to as recent as 2010. However, these migrations are not all documented in the same way. Often it is Durham’s growth as an economic center that is emphasized rather than the people who were affected by periods of demographic change.