Koloa, Birthplace of the Hawaiian Sugar Industry

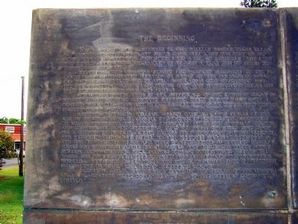

The Beginning. Near this site, on September 12, 1835, William Hooper began clearing 12 acres of land to plant sugar cane. The land was part of 980 acres leased by Hooper’s employer, Ladd & Co. of Honolulu. The land was leased from King Kamehameha III at $300 a year for 50 years beginning July 29, 1835.

Sugarcane grew in Hawaii before the Western discovery of the islands in 1788, apparently brought to Hawaii by the Polynesian voyagers who first settled the islands. But Ladd & Co.’s enterprise was the first major effort to cultivate cane and manufacture sugar for sale elsewhere in Hawaii and abroad.

Koloa Plantation thus is the birthplace of the Hawaiian sugar industry, which was the dominant economic force in Hawaii for over a century, and more than any other factor, shared the unique multi-ethnic society of this island state.

A native of Boston, William Hooper came to Hawaii in 1833 at the age of 24. He had no practical experience in agriculture mechanics or sugar processing and little knowledge of native Hawaiian culture and customs. It is not surprising that he had a difficult time starting a sugar plantation. Local chiefs felt threatened by his presence and withheld vital provisions, native workers had no experience in the use of western tools and were unaccustomed to working regular hours for pay. Cultivating rocky fields and building a water power system and a grinding mil in this remote region were formidable tasks for an inexperienced manager and his equally inexperienced workers, yet they preserved and the plantation grew. On November 16, 1836, the original mill began producing sugar.

A century and a half later many of the fields of the original Koloa Plantation were still growing cane for McBride Company Limited.

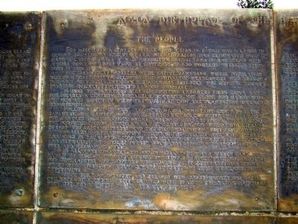

The Industry. Before Captain James Cook discovered Hawaii in 1778, the islands were isolated from most other parts of the world. Thereafter traders discovered large forests of sandalwood and began an export trade with the Orient. Whaling vessels soon made Hawaii a favored provisioning center.

Sugar gradually replaced sandalwood and whaling in the mid 19th century and became the principal industry in the islands until succeeded by the visitor industry in 1960. Sugarcane is well suited to Hawaii’s semi-tropical climate, which provides ample sunlight and heavy rainfall in windward and mountain areas. The settlement of California following the Gold Rush of 1849 created a growing market for Hawaiian sugar.

Other plantations soon followed Koloa. By 1883 more than 50 plantations were producing sugar on five islands. Sugar employment reached its high point of 56,630 in 1928. Cane cultivation peaked in the 1930s at approximately 255,000 acres. Record annual production of 1,234,121 tons of raw sugar was achieved in 1966.

As of 1985 sugar-per-acre yields were still rising. No area of the world produces more sugar per acre of per work hour than Hawaii.

Five major companies gradually emerged to provide marketing, supplies and other services for the plantations and eventually came to own and manage most of them. They became known as the Big Five. In order of their founding they are C. Brewer and Company Limited, Theo. H. Davies & Company Limited, Amfac Inc., Castle & Cooke Inc., and Alexander & Baldwin Inc.

In 1945 the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union was elected to represent most of the Hawaiian sugar workers. For many years they have been the most productive and richest paid agricultural workers in the world.

The People. For more than a century, sugar production in Hawaii was a labor intensive business. In recent years, mechanization has eliminated most manual labor. In 1984, Hawaii produced 1,061,591 tons of raw sugar with a work force of about 7500. By contrast, 56,630 workers produced 90,040 tons in 1928.

The first sugar workers were native Hawaiians, whose population declined drastically following the arrival of westerners, who brought diseases previously unknown in Hawaii. As a result, the growing sugar industry quickly experienced a labor shortage.

In 1852, the planters began recruiting laborers from China and for nearly a century thereafter searched the globe for hardy working men and women to whom the rough life of the plantation offered opportunity.

Following the Chinese the next major immigrant group was the Japanese. The Gannen-Mono, or first-year people, arrived in 1868 and the Kanyaku Imin, or government approved workers, in 1885. Next came the Portuguese from Madeira and the Azores in 1878; the Puerto Ricans in 1900; the Koreans in 1903; and the Filipinos in 1906, 1920, 1930, and 1946.

Smaller immigrant groups including the English and Scots began and arriving in the 1830s; Germans and Scandinavians from Norway, Sweden and Denmark in 1881; Poles in 1897; Spaniards in 1898, Black Americans in 1900; and Russians in 1909.

In all approximately 350,000 immigrant men and women came to Hawaii to work in the sugar industry. Some remained with the industry for generations while others worked out their contracts and found other occupations in Hawaii. Others returned to their homelands after retirement.

They built an industry and created new opportunities for their children. By blending their cultures with that of the native Hawaiians, they created a uniquely rich and varied society.

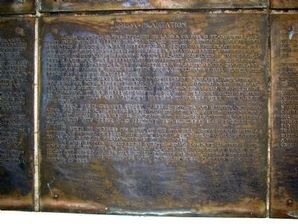

Koloa Plantation. Koloa Plantation was operated by Ladd & Co. for 13 years until January 1848, when Dr. Robert W. Wood became the new owner. In 1851, Dr. Wood appointed H. Hackfeld & Co. of Honolulu as agents for the plantation. In 1871, Paul Isenberg, manager of the Lihue Plantation, bought controlling interest in the plantation and six years later conveyed it to Judge Alfred S. Hartwell, who incorporated the company as the Koloa Sugar Company. By 1888, H. Hackfeld & Co. had acquired a majority of the shares and continued in control until 1918 when the Hackfeld and Koloa shares were bought by American Factors, Ltd.

These early years saw many innovations in plantation operation, including the development of Koloa Landing as a shipping port; start of a railroad system in 1882; purchase of a steam plow in 1893; construction of a hospital in 1910; improvements in irrigation including miles of ditches, artesian wells and a dam that created Waita Reservoir, the largest in Hawaii.

World War II created severe labor shortages and maintenance problems for Koloa Plantation’s aging factory and rail system. The postwar debts of Koloa could not be overcome. In January 1948 the plantation was merged with Grove Farm Company, established in 1864 by George N. Wilcox.

In order to process its cane at the Pa‘a Mill, Grove Farm bored a vehicular tunnel through the Haupu Range, built miles of all-weather roads, and doubled the capacity of the factory.

In January 1974, neighboring McBryde Sugar Company Limited, a subsidiary of Alexander & Baldwin, Inc., leased the factory and lands at Koloa and moved all its milling operations to that site. As of 1985, McBryde continued to cultivate cane in fields first planted by William Hooper in 1835.

The Mill Site. Ladd & Co. built its first sugar mill about half a mile from this site at a place called Maulili, where a dam was built to provide water power. Koa logs, set vertically, were used as grinding rollers. They quickly wore out. In 1837, a new mill was built nearby with a set of three horizontal iron rollers—the first arrangement of this kind in Hawaii.

The Maulili mill proved inadequate for the expanding plantation and in 1841 a new mill was buillt on this site, known then at Waihohonu. A new dam was built to provide power and a mill house, boiling house, sugar house, cart house and stable, and workmen’s houses were erected with a stone wall completely enclosing the five-acre site. This mill processed about 40 carts of cane per day from its own fields and independent growers nearby.

During the 1850s, centrifugal machines were installed to separate molasses from the sugar. In 1869, a steam engine was installed to grind the cane when the water failed. Other improvements were made periodically until 1897, when the factory was completely remodeled and modernized for the last time.

In 1913, Koloa Plantation build a new mill in Pa‘a, about a mile east of this monument site, where there was room for expansion. Some of the machinery was moved to the new factory and the monument site was abandoned after 72 years of operation.

Visible today are the remnants of the boiling house built in 1841. The stone chimney was the furnace, fueled by the bagasse, the residue of the cane plant after grinding. Flues directed the hot gasses to boiling pans in which cane juice was boiled until sugar crystals formed. After cooling the mass of crystals was separated in a centrifuge to produce raw or unrefined sugar.

The Sculpture. The concrete sculpture is circular, to suggest a mill stone opened to reveal the bronze figures inside. It is oriented to call attention to the remnants of the 1841 mill. The figures represent the eight principal ethnic groups that created the sugar industry and Hawaii’s unique society.

The artist, Jan Fisher, says: “I hoped to capture the faces and stances, the dignity and strength of these people. The workers are dressed as they might have been during their earliest years in Hawaii. The group expresses the cooperation between diverse peoples which made possible the development of the sugar industry and perpetuated the aloha spirit of the native Hawaiians.”

The first figure on the left is a Hawaiian, representing the first sugar workers. He wears a malo, holds an o‘o and sits next to his poi dog. In the background, riding upon a horse, is a Caucasian, representing the North American and European entrepreneurs and managers who started and developed the industry. Next is a Puerto Rican man carrying sugarcane. Beside him, a Chinese man squats to pick up his hoe, attired in laborer’s clothing of the Ming Dynasty. Then a Korean woman carries a large bundle of cane. A Japanese woman wears chikatabis to protect her feet and her face is shielded from the sun by a traditional hat. On her left a Portuguese woman stands barefoot, with headgear well suited for carrying any needful thing. Finally a Filipino, carrying a cane knife, represents the last major emigrant group to join the Hawaiian sugar industry.

The Monument. This monument was built under the direction of the Hawaii Sugar Monument Committee as part of the observance of the 150th anniversary of the Hawaiian sugar industry and Koloa Plantation held in Koloa on July 27, 1985.

Committee members were: (list of names)

Major funding for the monument was provided by: (list of names) Site donated by the Knudsen family.

Also contributing: (list of names)

In-Kind contributions were received from: (list of names)

The Artist. Jan Gordon Fisher.

Design and execution of the monument and sculpture are the work of Jan Fisher, of Brigham Young University—Hawaii, in Laeie, Oahu. He was awarded the commission by the Hawaii Sugar Monument Committee in competition with other local artists. He views the work as a personal expression of aloha to the people of Hawaii. “The figures pay tribute to the Hawaiians and to the immigrants who came to work for the sugar industry. Many of their descendants are my friends and colleagues.”