Borderland - Pueblo / Railroads - Pueblo Country

Panel 1

Borderland

The 1819 Adams-Oñis Treaty fixed the boundary between the U.S. and Spain at the Arkansas River, formalizing a centuries-old convention - the Arkansas had always been a border. Neighboring Indian tribes fronted tensely on this crucial waterway, whose wealth of resources (water, timber, pasture, game) were essential for survival. The colonial powers, too, jostled for control of the river, which came to represent the proverbial line in the sand. Any breach drew the fiercest resistance. Spain was particularly vigilant, ignoring French and American travelers north of the Arkansas but treating all who ventured south of it (including Zebulon Pike) as hostile invaders. With America's 1848 conquest of northern Mexico and the removal of the Arapahos and Cheyennes in 1865, the river finally ceased to divide. For the first time in perhaps 1,000 years, the Arkansas served a single country. Today, it remains a cultural border of the American Southwest.

Crossroads of the Arkansas

Pueblo sits at the intersection of two ancient thoroughfares - the Arkansas River, gateway to the mountains and a key prairie highway, and Fountain Creek, part of the long north-south road along the Front Range of the Rockies. Utes, Plains Apaches, Comanches, Kiowas, Arapahos, and Cheyennes all frequented the area around present-day Pueblo; the Spanish and French sent explorers here; and the site's steady traffic made it a perfect location for nineteenth-century traders from Mexico and the United States. By the 1890s the railroads, built along the two timeless footpaths, were carrying immigrant workers from around the world to Pueblo. Today this welcoming junction of mountain and plain bears the influence of more than thirty nations.

Images found on this panel:

Photo of Charles Autobees

(Caption) Settling near Pueblo in 1853, mountain man and trader Charles Autobees personified the integration of cultures in the Upper Arkansas Valley. Family and friends crossed all racial, national, and ethnic lines, and he spoke English, Spanish, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Sioux, and Navajo fluently.

Colorado Historical Society

Map with Indian tribes

(Caption) Borderlands, c. 1850

Colorado Historical Society

Photo of Pike:

(Caption) While exploring the United States's new southern boundary, Lt. Zebulon M. Pike and his entourage camped at the fork of the Arkansas River and Fountain Creek in 1805. Here they erected a crude stockade for protection - possibly the first structure built by U.S. citizens in Colorado.

Colorado Historical Society

Photo: Birds eye view of Pueblo

(Caption) The Arkansas acted as a borderland of sorts during Pueblo's development. In this map, South Pueblo (incorporated in 1873) sits on the far side of the Arkansas River and Pueblo (incorporated in 1870) is in the foreground. In 1882 Central Pueblo incorporated on a small area of land on the north side of the river. The three merged in 1886, creating one of the state's largest cities.

Colorado Historical Society

Panel 2

Pueblo

Pueblo's frontier precursor, El Pueblo (1842-1854), counted African Americans, Mexicans, Anglos, and Indians among its ever-changing residents. The city that eventually grew here boasted even greater ethnic diversity. Vast waves of immigrants came to Pueblo in the late nineteenth century, landing in Smelter Hill's shanties, then moving up as their prospects improved. These new Americans - Italians, Irish, Slovenians, Welsh, Germans, Greeks, Russians, Southern and Eastern European Jews, and Japanese - found plentiful work in the smelters and rail yards, and they added immeasurably to the city's cultural life. Pueblo's Italian stonemasons constructed many of Pueblo's buildings; Hispanos contributed to livestock raising practices and labor for the railroad; the first Slovakian Eastern Orthodox church in Colorado was built in Pueblo in 1899; and all groups had thriving businesses, newspapers, and civic organizations. Thousands came to Pueblo in search of the American dream of freedom and opportunity. While for some the search was fruitless, for many more the dream proved a reality. Today many of their descendants are civic and cultural leaders.

Pueblo's lavish Mineral Palace (est. 1891) featured shrines to King Coal and Queen Silver. How apt - for coal was literally king in Pueblo, and hard metals made the town glitter. Incorporated in 1860 as a ranching and supply town, Pueblo soon became Colorado's capital of heavy industry. Its furnaces glowed around the clock, employing 8,000 workers and producing such quantities of iron and steel that the city grew famous as the "Pittsburgh of the West." But the catastrophic flood of 1921 staggered Pueblo, and the Great Depression shuttered many of its businesses. By 1943 the Mineral Palace was gone, along with the wealth it embodied. Pueblo began to retool in the 1980s, mining resources such as art, culture, recreation, and tourism to manufacture a new age of prosperity.

Photographs found on this panel:

Largest Photo: Mineral Palace Interior

Sporting a ninety-foot-high ceiling with twenty-eight domes (each painted with a different Colorado wildflower), Pueblo's Mineral Palace lavishly celebrated the state's mineral wealth. The stage represented a grotto with stalactites and stalagmites.

Colorado Historical Society

2nd Largest Photo: Newsboys

Of the over 127 newspapers that have been published in Pueblo, more than thirty were foreign-language papers - proof of a literate immigrant population.

Courtesy Pueblo Library District

Photo: Drawing of El Pueblo

El Pueblo offered guns, powder, beads, and trade cloth to customers on both sides of the Arkansas River. At its peak, about 150 men, women, and children resided here.

Courtesy Omaha World-Herald Quesenbury Sketchbook

Photo: Man, Lady, Saddles:

By the turn of the twentieth century, Pueblo was known as the "cowboy saddle capital" due to the quality of Robert Frazier's (left) product and those of the city's other two major saddle makers, Samuel Gallup and Robert Flynn.

Courtesy Pueblo Library District

Photo: Pineapple Salesman:

With some settling here as early as the 1860s, Pueblo's Jewish community has deep roots in the area. Max Stein (standing to the right in 1910) ran a wholesale food supply business in Pueblo. His family continued to own it until the early twentieth-first century.

Courtesy Pueblo Library District

Panel 3

Railroads

Pueblo's leaders put up $50,000 to lure the Denver & Rio Grande to town in 1872. What an investment! The railroad not only transported cattle, but fed ores to local smelters that fashioned these raw materials into rails, spikes, and pistons. D&RG magnate William Jackson Palmer founded Pueblo's first steel plant, which later evolved into mighty Colorado Fuel and Iron - by 1900 among the world's largest steel producers. Four other railroads connected Pueblo to distant markets, fueling commerce and employing thousands of workers. The industry sagged during the Great Depression but bounced back briefly during World War II, when trains delivered munitions to the Pueblo Army Ordnance Depot. Though the railroads' passenger heyday ended after the war, freight cars still rumble through Pueblo, a routine nearly as old as the city itself.

Union Avenue and Depot

Erected in 1889, Pueblo's Union Depot was an emblem of civic pride, complete with Romanesque architecture, stained-glass windows, and a 150-foot-high clock tower. For sheer grandeur, few Colorado buildings could match it. And few streets could match the bustle of Union Avenue, a teeming promenade lined with hotels, shops, and restaurants. It was the flourishing heart of a flourishing city. However, the 1921 flood (which soaked the depot in eleven feet of water), the Great Depression, and the railroad's postwar decline took their toll; by 1971 Union Depot stood empty, and the once-handsome Avenue was vacant and deteriorating. But Puebloans fought to restore luster to the neighborhood. Designated a National Historic District in 1982, Union Avenue is again a prestige destination, and the rehabilitated depot sparkles, wearing its heritage proudly.

Photographs found on this panel:

Photo of Union Avenue

(Omitted Caption) In 1889 the Pueblo City Council passed an ordinance making it a misdemeanor to drive mules, horses, or other animals through city streets or alleys any faster than six miles per hour.

Colorado Historical Society

Photo of Union Avenue Flooded

One of the significant changes wrought by the1921 flood on Union Avenue was the emergence of automobiles. The flood destroyed the area's livery stables, and after 1921 horses were seldom seen on the thoroughfare.

Colorado Historical Society

Photo of Train with Banners

Industrial Parade, 1912

Colorado Historical Society

Photo of Station and Trains

In 1892 fifty-one trains a day came through Union Depot, 164,718 pieces of baggage were handled, and 103,114 tickets totaling $568,639 were sold.

Colorado Historical Society

Panel 4

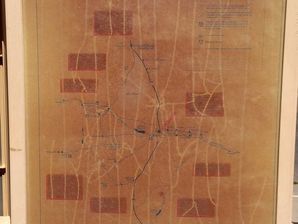

Map: Pueblo Country